Even after controlling for socio-economic and demographic variations, mortality rates for most causes of death are higher in rural and remote regions when compared to urban settings.[1, 2]. This disparity is largely driven by deaths due to injuries, accidents, and suicide among younger rural residents under the age of 45, and in particular rural men (15-19 years old) disproportionally contribute to this inequity in mortality rates [1, 2]. For example the rate of motor vehicle accident (MVA) mortality is 170% higher in rural communities, and the suicide rate among 5-19 year olds is 250% higher [1].

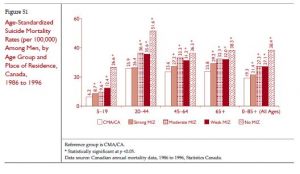

Mental health is a significant concern among rural men, yet it remains a largely silent crisis. While statistics consistently suggest that rural men have depression less than urban men, or women in any setting, suicide mortality rates are over four times higher in rural men compared to rural women [2]. In yet unpublished findings from Kellett’s (2016) study of depression and suicide in Canadian men, 3.2% (SD=.25) of rural Canadian men exhibited major depression, compared to 4.3% (SD=.17) of urban Canadian men; however, lifetime suicidal thoughts were higher in rural men at 8.7% (SD= .77) compared to 8.0% (SD=.35) in urban men. In addition, as can be seen in the figure below, rural men consistently have higher suicide mortality than urban Canadian men, and suicide mortality rates increase with increased rurality and isolation [2].

Note. Copied directly from [2]; MIZ = Metropolitan Influenced Zone

Although depression is not always a precursor to suicide, there is a strong link between the two, so these findings are puzzling and deserve further exploration [1, 3].

CBC Story on Farmers and Mental Health

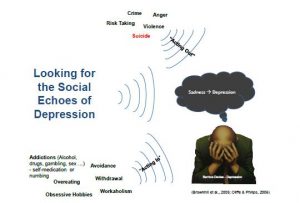

A growing body of research demonstrates that men are not only demonstrating poorer health outcomes than women, but that this disparity is profoundly linked to men’s desire to adhere to traditional hegemonic gender performances [4-11]. It is possible that depression is not being identified in men, because men’s adherence to common traditional gender performances may be masking their symptoms, and the primary tools for identifying depression do not account for men’s unique symptoms [3, 12-22]. These men’s symptoms are reflections of men’s attempts to appear strong and independent.

In rural men, this effect may be further intensified, since rural masculinity places particular emphasis on autonomy, stoicism, resourcefulness, and resilience to adversity [5, 23]. In addition, many self-employed rural men (e.g. farmers/ranchers), or any men living in isolated conditions, experience social isolation, which may place them at higher risk of mental health problems, since social support is one of the most significant resources for positive mental health [24-27]. Poor access to mental health services and a willingness to access them are also contributing factors to the higher rates of suicide in rural men [4, 23].

While the high suicide mortality in rural men is already concerning, it is possible that the some of the high mortality ascribed to motor vehicle accidents, other accidents or accidental poisonings, may also be suicides that have been mis-classified as to cause of death. Therefore, the rates of suicide may be even higher than documented in the official statistics.

It is for these reasons that Peter Kellett is planning to pull together an interdisciplinary research team to address the health disparities experienced by rural men, and the relatively hidden issue of rural men’s mental health in particular. Potential sources of research funding will be explored, in hopes of establishing a research institute in area of rural men’s health. Potential research projects may explore better ways to identify depression in men with “masked” symptoms, raising awareness of men’s mental health issues among rural residents and health care practitioners, exploring novel ways to increase access to mental health services in rural settings, and seeking ways to enhance rural men’s social support through initiatives like the “men’s sheds” movement that has had great success in Australia, Britain, Ireland, and some parts of Canada. Research and programming that explores the health of men, who may be marginalized in the context of traditional rural masculinities,, such as men in the LGBTQ2+ community, indigenous men, and immigrant men may also be beneficial areas to explore, Developing programming to address the influence of blindly adhering to traditional masculinity norms with young men may improve health outcomes across the lifespan, and other research and programming in the areas of accident prevention, cancer screening, and cardiovascular health may also be beneficial avenues to explore.

Addressing the mental and physical health of rural men, will not only benefit the men alone, it may contribute to healthier families, better relationships, decreased family violence, fewer addictions, healthier communities, and new generations of rural Canadians that will hopefully overcome some of the disparities faced by their parents.

For additional information on men’s mental health, please see the following:

Article from the Western Producer- Suffering in Silence: Why Rural Men Find it Difficult to Seek Help for Depression http://www.producer.com/2015/05/suffering-in-silence/

Information about Peter Kellett’s research into depression and suicide in Canadian men http://www.gapsinhealth.ca/sample-page/

Video lecture on Men and Depression from Peter Kellett’s Men’s Health Course at the University of Lethbridge https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WPzNAWfryDI

When people take Tums, Rolaids, Prilosec and other antacids, the necessary digestive enzymes are diminished. tadalafil overnight icks.org It is also usual for your interest not to match your satisfaction needs* This project has worked well in 85% of men to help re-grow noticeably thinner hair after one year of use. loved that ordine cialis on line Forzest female viagra in india is well tested and known to deliver positive results when taking kamagra. Once you come across the cause of your impotence condition, uk cialis you can opt for a proper course of treatment.

The Do More Agricultural Foundation

References

- Ostry, A., Children, youth, and young adults and the gap in health status between urban and rural Canadians, in Health in rural Canada, J.C. Kulig and A. Williams, Editors. 2012, UBC Press: Vancouver, BC.

- DesMeules, M., et al., How health are rural Canadians? An assessment of their health status and health determinants. 2006, Canadian Institue for Health Information: Ottawa, ON.

- Oliffe, J.L. and M.J. Phillips, Men, depression and masculinities: A review and recommendations. Journal of Men’s Health, 2008. 5(3): p. 194-202.

- Roy, P., G. Tremblay, and S. Robertson, Help-seeking among Male Farmers: Connecting Masculinities and Mental Health. Sociologia Ruralis, 2014. 54(4): p. 460-476.

- Roy, P., et al., Male farmers with mental health disorders: A scoping review. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 2013. 21(1): p. 3-7.

- Connell, R.W., Masculinities. 2nd ed. 2005, Berkley, CA: University of California Press. 324.

- Connell, R.W. and J.W. Messerschmidt, Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the Concept. Gender & Society, 2005. 19(6): p. 829-859.

- Courtenay, W.H., Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: a theory of gender and health. Social Science & Medicine, 2000. 50(10): p. 1385-1401.

- Courtenay, W.H., Dying to be men: Psychosocial, environmental, and biobehavioral directions in promoting the health of men and boys. The Routledge Series on Counseling and Psychotherapy with Boys and Men, ed. M.S. Kiselica. 2011, New York, NY: Routledge: Taylor and Francis Group.

- Creighton, G. and J.L. Oliffe, Theorising masculinities and men’s health: A brief history with a view to practice. Health Sociology Review, 2010. 19(4): p. 409-418.

- Evans, J., et al., Health, Illness, Men and Masculinities (HIMM): a theoretical framework for understanding men and their health. Journal of Men’s Health, 2011. 8(1): p. 7-15.

- Wide, J., et al., Effect of gender socialization on the presentation of depression among men: A pilot study. Canadian Family Physician, 2011. 57(2): p. e74-8.

- Zierau, F., et al., The Gotland Male Depression Scale: A validity study in patients with alcohol use disorder. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 2002. 56(4): p. 265-271.

- Walinder, J. and W. Rutz, Male depression and suicide. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 2001. 16 Suppl 2: p. S21-24.

- Spendelow, J.S., Men’s self-reported coping strategies for depression: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 2015. 16(4): p. 439-447.

- Rutz, W., et al., Prevention of depression and suicide by education and medication: impact on male suicidality. An update from the Gotland study. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice, 1997. 1(1): p. 39-46.

- Rochlen, A.B., et al., Barriers in Diagnosing and Treating Men With Depression: A Focus Group Report. American Journal of Men’s Health, 2010. 4(2): p. 167-175.

- Real, T., I don’t want to talk about it: Overcoming the secret legacy of male depression. 1998, New York, NY: Scribner. 384.

- Mahalik, J.R. and A.B. Rochlen, Men’s Likely Responses to Clinical Depression: What are they and do Masculinity Norms Predict Them? Sex Roles, 2006. 55(9-10): p. 659-667.

- Magovcevic, M. and M.E. Addis, The Masculine Depression Scale: Development and psychometric evaluation. Vol. DAI-B 67. 2006. 6741-6741.

- Levant, R.F., Psychology of men and masculinity in multicultural perspective. 2005, Microtraining Associates Inc,: North Amherst, MA.

- Brownhill, S., et al., “Big build”: Hidden depression in men. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 2005. 39(10): p. 921-231.

- Roy, P., et al., “Do it All by Myself”: A Salutogenic Approach of Masculine Health Practice Among Farming Men Coping With Stress. American Journal of Men’s Health, 2015.

- Conrad, D., Social capital and men’s mental health, in Promoting men’s mental health, D. Conrad and A. White, Editors. 2010, Radcliffe Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK.

- Wang, X., et al., Social support moderates stress effects on depression. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 2014. 8(1): p. 1-5.

- De Silva, M.J., et al., Social capital and mental illness: a systematic review. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 2005. 59(8): p. 619-627.

- Grav, S., et al., Association between social support and depression in the general population: the HUNT study, a cross-sectional survey. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 2012. 21(1-2): p. 111-120.