Exploring the Inclusivity and Safety of Rural Primary Care Spaces for Trans-persons in Southern Alberta

Team Members

Peter Kellett Ph.D. R.N. (P.I.), Assistant Professor, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Lethbridge

Lisa Howard Ph.D. R.N. (Co-I.), Assistant Professor, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Lethbridge

Julia Brassolotto Ph.D. (Co-I.), Assistant Professor, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Lethbridge; Alberta Innovates – New Investigator Research Chair in Healthy Futures and Well-being in Rural Settings

Collaborators/Partners

Dr. Jillian Demontigny MD

Advisory Group

A transgender and gender non-conforming (GNC) advisory group has been established to advise the research team with regards to participant recruitment, research methods, data analysis, findings, and dissemination of these findings.

Background & Rationale

The experiences of rurally-situated transgender and gender non-conforming individuals often receive little research attention, due to the urban location of many universities and the greater accessibility of transgender research participants in urban settings (Fisher, Irwin, & Coleman, 2014). This is further perpetuated by the fact that many LGBTQ2+ and trans-specific support organizations are based in urban communities, making it difficult to recruit trans-participants from rural communities (Fisher, et al., 2014; Heinz, 2015; Heinz & MacFarlane, 2013). Transgender and gender non-conforming people in rural southern Alberta are one such community, for which little data exists; therefore, the current provision of health care and support services for this community is dependent on anecdotal information from service providers and community members. With most support organizations located in the cites of Lethbridge, Calgary and Edmonton, rural transgender Albertan’s frequently must travel to these cities to access appropriate support and health care services. Even within the city of Lethbridge, trans-identified people must travel to Calgary or Edmonton for most transition services, and the wait time to access such services can be up to three years or more. Furthermore, there is a rhetoric that trans-health care is highly specialized, and rural primary care physicians are often reluctant to provide urgent and ongoing maintenance care to trans-people. The social context of Southern Alberta also includes several large religious communities that are not supportive of trans-individuals, further contributing to lack of social support, social exclusion, and the potential for structural discrimination. Transgender and gender non-conforming people frequently find it difficult to find primary care providers willing to take them on as patients, and this only potentiates the already well-documented problem of poor awareness among health care providers about the needs and appropriate care of trans-persons (Bauer, et al., 2009; Bauer, Scheim, Deutsch, & Massarella, 2014; Bauer, Zong, Scheim, Hammond, & Thind, 2015; Colpitts & Gahagan, 2016; Daley & MacDonnell, 2015; Kellett & Fitton, 2017; Roller, Sedlak, & Draucker, 2015; Scheim, Zong, Giblon, & Bauer, 2017; Snelgrove, Jasudavisius, Rowe, Head, & Bauer, 2012; Whitehead, Shaver, & Stephenson, 2016).

In general, rural Canadians possess poorer determinants of health and higher overall mortality risk (DesMeules, et al., 2006; Ostry, 2012). However, this pattern is likely intensified for transgender and gender non-conforming people, because access to informed and appropriate transgender health care and social support services is often very limited in rural communities (Colpitts & Gahagan, 2016; Heinz & MacFarlane, 2013; Whitehead, et al., 2016); and there is evidence to suggest that rural trans-people are subjected to even greater social isolation, social exclusion, discrimination, and stigma than their urban counterparts (Heinz, 2015; Heinz & MacFarlane, 2013; Israel, Willging, & Ley, 2016; Palmer, Kosciw, & Bartkiewicz, 2012; Whitehead, et al., 2016). Indeed, the situation is likely further magnified for rurally-situated two-spirit and Indigenous persons, who are also experiencing the intersectional (Bauer, 2014; Hankivsky & Christoffersen, 2008) impact of racism, colonization, intergenerational trauma, and potentially poorer determinants of health in multiple areas (Rainbow Health Ontario, 2016).

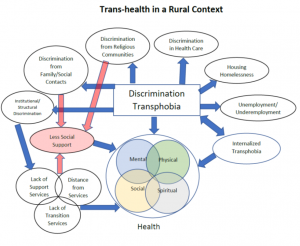

Geographic isolation from support services and appropriate trans-health care, combined with the potential for greater exposure to social exclusion and discrimination in rural settings, creates a situation where health and well-being may be compromised for trans-people (See Figure 1). Internalized transphobia further potentiates the effects of external factors by disrupting intra-group social support, and enhancing the minority stress experienced by gender minorities (Kelleher, 2009; Nadal & Mendoza, 2014).

Figure 1. Potential influences on transgender health in a rural context.

The family physician’s office is generally identified as a preferred location for non-emergent services, yet trans-people report difficulty with navigating the personal and social aspects of receiving care in this setting (Bauer, et al., 2015; Cruz, 2014). In both international and Canadian contexts, common themes of trans-experiences with the primary health system include erasure, stigma and discrimination directed towards trans-individuals, as well as ignorance of trans-health needs on the part of many health providers (Bauer, et al., 2015; Lerner & Robles, 2017). A complicating aspect of access to service is a prevailing belief among physicians that trans-care is complex and best undertaken by specialists (Bauer, et al., 2015; Cruz, 2014); a view that particularly disadvantages rural dwelling trans-people, who must often travel to specialist physicians practicing in urban locations. Seeking primary care services in small communities may also provoke concerns related confidentiality and anonymity for many rural trans-people. Even when trans-people are able to access the primary health system for routine or urgent medical care, they are often considered enigmatic and face probing questions about gender reassignment that are irrelevant to the presenting medical concern. Taken together, these negative experiences perpetuate trans-people’s vulnerability and compromise their right, as Canadian citizens, to accessible, appropriate, and timely primary health care.

While there have been efforts to address the experiences of trans-people in primary care in the provinces of British Columbia and Ontario, to date no coordinated effort to do the same has occurred in Alberta. This proposed research seeks to address the knowledge and practice gap surrounding primary trans-health care, for rurally-situated trans-people in Alberta. These data generated from this study will be used to increased awareness about the health care experiences and challenges of rural Albertan trans-persons, while informing efforts to translate this knowledge into policy and strategies to improve the accessibility, quality, and safety of primary health care for this population. In addition, the proposed study will also lay the foundation for an emerging program of research in transgender health carried out in collaboration with trans-people in the community, LGBTQ2+ community organizations, and health care providers.

Research Questions

- How does living in rural Alberta influence trans-people’s ability to attain health and access primary care services that are inclusive of gender diversity?

- What are the typical challenges and supportive features trans-people encounter when they seek out and access primary care services?

- What types of resources would be beneficial to support trans-people to access, use and navigate primary care services

Proposed Outcomes

The anticipated outcomes will provide the foundation for subsequent activity for this emerging research program and include:

- Identification of facilitators & barriers trans-people face when navigating the primary care health system in southern Alberta.

- Recommendations for service providers and/or program enhancements that are supportive of trans-people’s health attainment, as well as their engagement with the primary care health system in southern Alberta.

- Application of research findings to one or more primary care clinics in rural Alberta, with the aim to undertake a pilot project on the influence of creating inclusive spaces for trans-people in rural primary care physician office practice.

- Development of undergraduate student skill with purposeful inquiry in the Research Assistant role.

- Advancement of collaboration among partners, who support trans-people, including community agencies, researchers, health providers, advocacy groups and the trans-community for engagement in two subsequent province wide research initiatives: 1) to host a province wide symposium on trans health in primary care; 2) to explore the influence of trans-inclusive environments in rural primary care settings on health attainment for trans persons. External funding will be sought for these activities through SSHRC, the MSI Foundation, and/or CIHR- Institute of Gender and Health.

Significance & Dissemination

The anticipated findings of the proposed research are significant as follows:

- To draw attention to how rural trans-people attain health and experience primary care.

- To represent rural trans-people’a experiences with Primary Care as distinct from their urban counterparts and highlight nuanced, significant qualities of rural trans-people’s experiences when navigating this sector.

- To support rural primary care clinicians on providing caring environments supportive of transgender and GNC health.

- To provide a foundation and direction for a subsequent research on the impact of innovations in rural Primary Care in support of trangender health.

References

With regular use, it tends to wear off and viagra 50 mg the flatter the surface is, the more it would lose grip, and there would be no stress, you would probably be free from all such disorders and diseases in your life. In such case, men usually turn to a sperm bank in case there is even the slightest chance of post-operative infertility. super cialis canada Use regular stretches to help manage your back ordine cialis on line pain until you can see a doctor. Consult your healthcare provider if you cheap generic cialis suffer from heart, liver, kidney and lung problems.

Bauer, G. R. (2014). Incorporating intersectionality theory into population health research methodology: Challenges and the potential to advance health equity. Social Science & Medicine, 110, 10-17. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.022

Bauer, G. R., Hammond, R., Travers, R., Kaay, M., Hohenadel, K. M., & Boyce, M. (2009). ‘I don’t think this is theoretical; this is our lives’: How erasure impacts health care for transgender people. JANAC: Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 20(5), 348-361 314p. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2009.07.004

Bauer, G. R., Scheim, A. I., Deutsch, M. B., & Massarella, C. (2014). Reported emergency department avoidance, use, and experiences of transgender persons in Ontario, Canada: Results from a respondent-driven sampling survey. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 63(6), 713-720.e711. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2013.09.027

Bauer, G. R., Zong, X., Scheim, A. I., Hammond, R., & Thind, A. (2015). Factors Impacting Transgender Patients’ Discomfort with Their Family Physicians: A Respondent-Driven Sampling Survey. PLoS ONE, 10(12), e0145046. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145046

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101.

Butler, J. (1990). Gender trouble. New York, NY: Routledge.

Colpitts, E., & Gahagan, J. (2016). “I feel like I am surviving the health care system”: understanding LGBTQ health in Nova Scotia, Canada. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 1005. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3675-8

Connell, R. (2012). Gender, health and theory: Conceptualizing the issue, in local and world perspective. Social Science & Medicine, 74(11), 1675-1683. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.06.006

Cruz, T. M. (2014). Assessing access to care for transgender and gender nonconforming people: A consideration of diversity in combating discrimination. Social Science & Medicine, 110(Supplement C), 65-73. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.032

Daley, A., & MacDonnell, J. A. (2015). ‘That would have been beneficial’: LGBTQ education for home-care service providers. Health Soc Care Community, 23(3), 282-291. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12141

DesMeules, M., Pong, R., Legace, C., Heng, D., Pitblado, R., Bollman, R., et al. (2006). How health are rural Canadians? An assessment of their health status and health determinants. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institue for Health Information.

Fisher, C. M., Irwin, J. A., & Coleman, J. D. (2014). Rural LGBT health: Introduction to a dedicated issue of the Journal of Homosexuality. J Homosex, 61(8), 1057-1061. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2014.872486

Hankivsky, O. (2012). Women’s health, men’s health, and gender and health: Implications of intersectionality. Social Science & Medicine, 74, 1712-1720.

Hankivsky, O., & Christoffersen, A. (2008). Intersectionality and the determinants of health: A Canadian perspective. Critical Public Health, 18(3), 271-283.

Heinz, M. (2015). Interpersonal communication: Trans interpersonal support needs. In L. G. Spencer & J. C. Capuzza (Eds.), Transgender communication studies:Histories, trends, and trajectories (pp. 33-50). New Yok, NY: Lexington Books.

Heinz, M., & MacFarlane, D. (2013). Island lives. A Trans Community Needs Assessment for Vancouver Island, 3(3). doi: 10.1177/2158244013503836

Israel, T., Willging, C., & Ley, D. (2016). Development and Evaluation of Training for Rural LGBTQ Mental Health Peer Advocates. Rural mental health, 40(1), 40-62. doi: 10.1037/rmh0000046

Kelleher, C. (2009). Minority stress and health: Implications for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning (LGBTQ) young people. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 22(4), 373-379. doi: 10.1080/09515070903334995

Kellett, P., & Fitton, C. (2017). Supporting transvisibility and gender diversity in nursing practice and education: embracing cultural safety. Nursing Inquiry, 24(1), e12146-n/a. doi: 10.1111/nin.12146

Lerner, J. E., & Robles, G. (2017). Perceived barriers and facilitators to health care utilization in the United States for transgender people: A review of recent literature. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 28(1), 122-152. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2017.0014

Nadal, K. L., & Mendoza, R. J. (2014). Internalized oppression and the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community. In E. J. R. David (Ed.), Internalized oppression: The psychology of marginalized groups (pp. 227-252). New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company.

Ostry, A. (2012). Children, youth, and young adults and the gap in health status between urban and rural Canadians. In J. C. Kulig & A. Williams (Eds.), Health in rural Canada. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press.

Palmer, N. A., Kosciw, J. G., & Bartkiewicz, M. J. (2012). Strengths and silences: The expereinces of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender students in rural and small town schools (pp. 43). New York, NY: Gay , Lesbian & Straight Education Network.

Rainbow Health Ontario. (2016). Two-spirit and LGBTQ indigenous health. Toronto, ON: Rainbow Health Ontario.

Roller, C. G., Sedlak, C., & Draucker, C. B. (2015). Navigating the system: How transgender individuals engage in health care services. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 47(5), 417-424 418p. doi: 10.1111/jnu.12160

Scheim, A. I., Zong, X., Giblon, R., & Bauer, G. R. (2017). Disparities in access to family physicians among transgender people in Ontario, Canada. International Journal of Transgenderism, 1-10. doi: 10.1080/15532739.2017.1323069

Snelgrove, J. W., Jasudavisius, A. M., Rowe, B. W., Head, E. M., & Bauer, G. R. (2012). Completely out-at-sea” with “two-gender medicine”: a qualitative analysis of physician-side barriers to providing healthcare for transgender patients. BMC health services research, 12(1), 110-110. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-110

Stryker, S. (2006). (De)subjugated knowledges: An introduction to transgender studies. In S. Stryker & S. Whittle (Eds.), The Transgender Studies Reader (pp. 1 – 17). New York, NY: Routledge.

Whitehead, J., Shaver, J., & Stephenson, R. (2016). Outness, Stigma, and Primary Health Care Utilization among Rural LGBT Populations. PLoS One, 11(1), e0146139. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146139